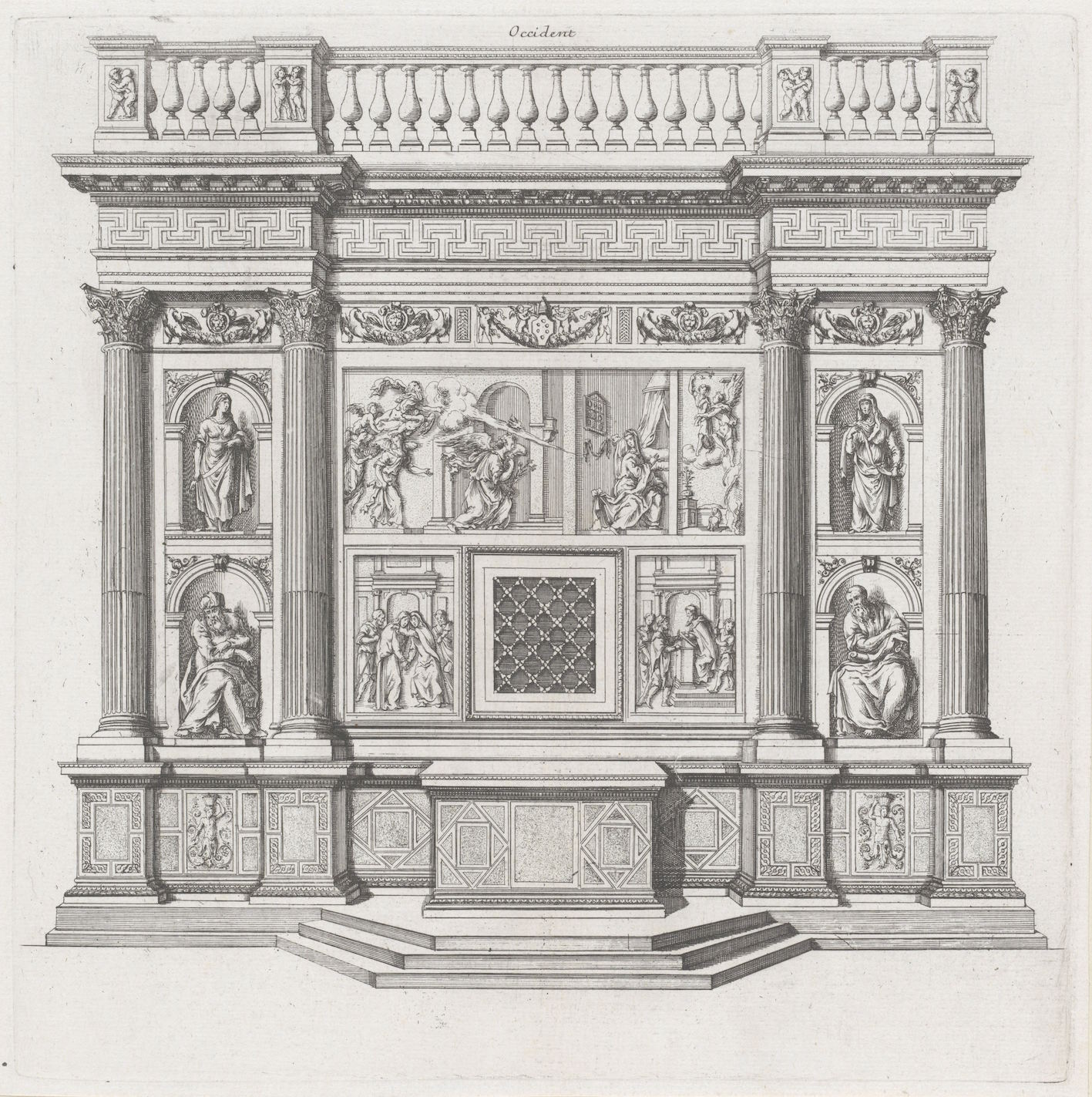

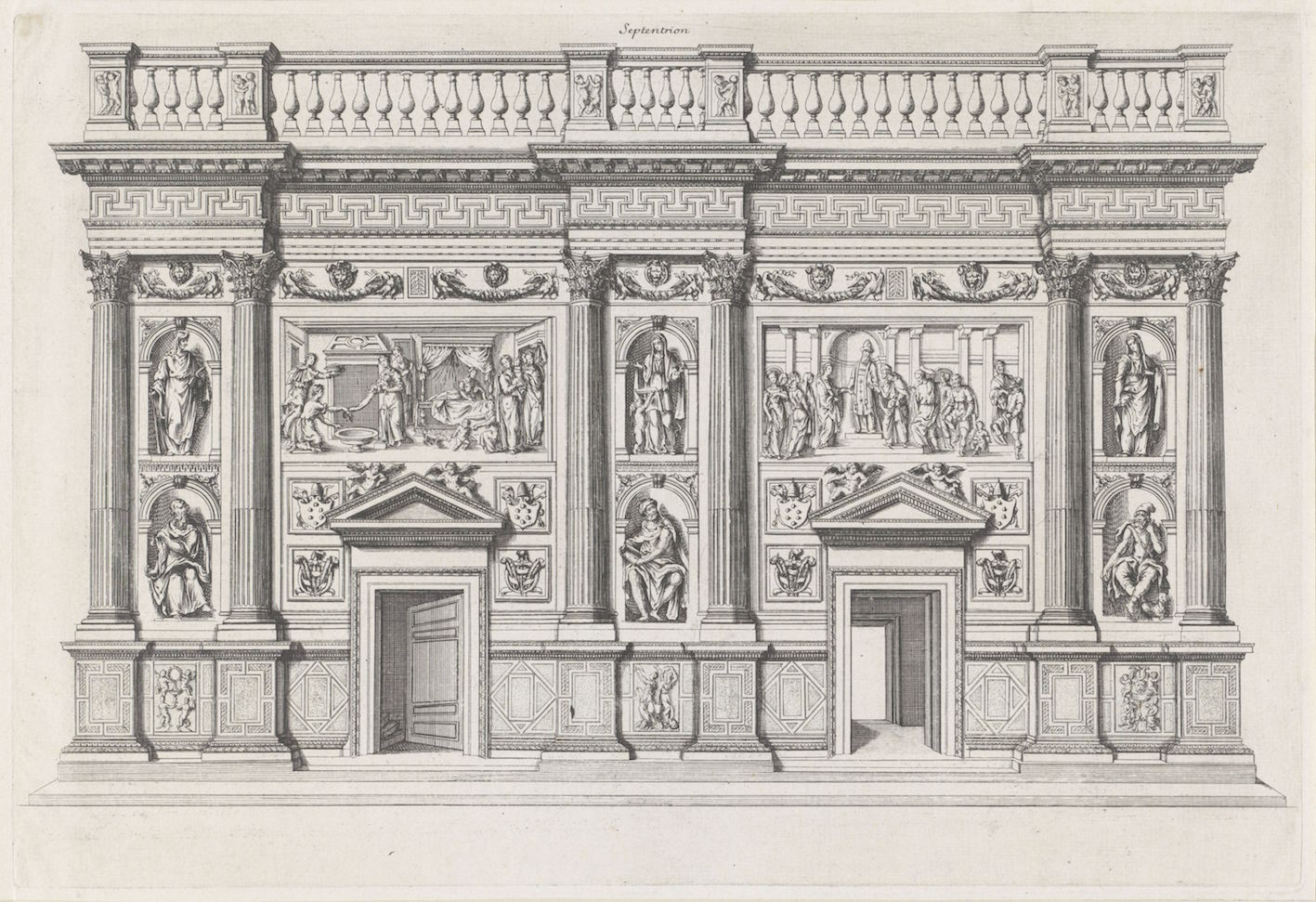

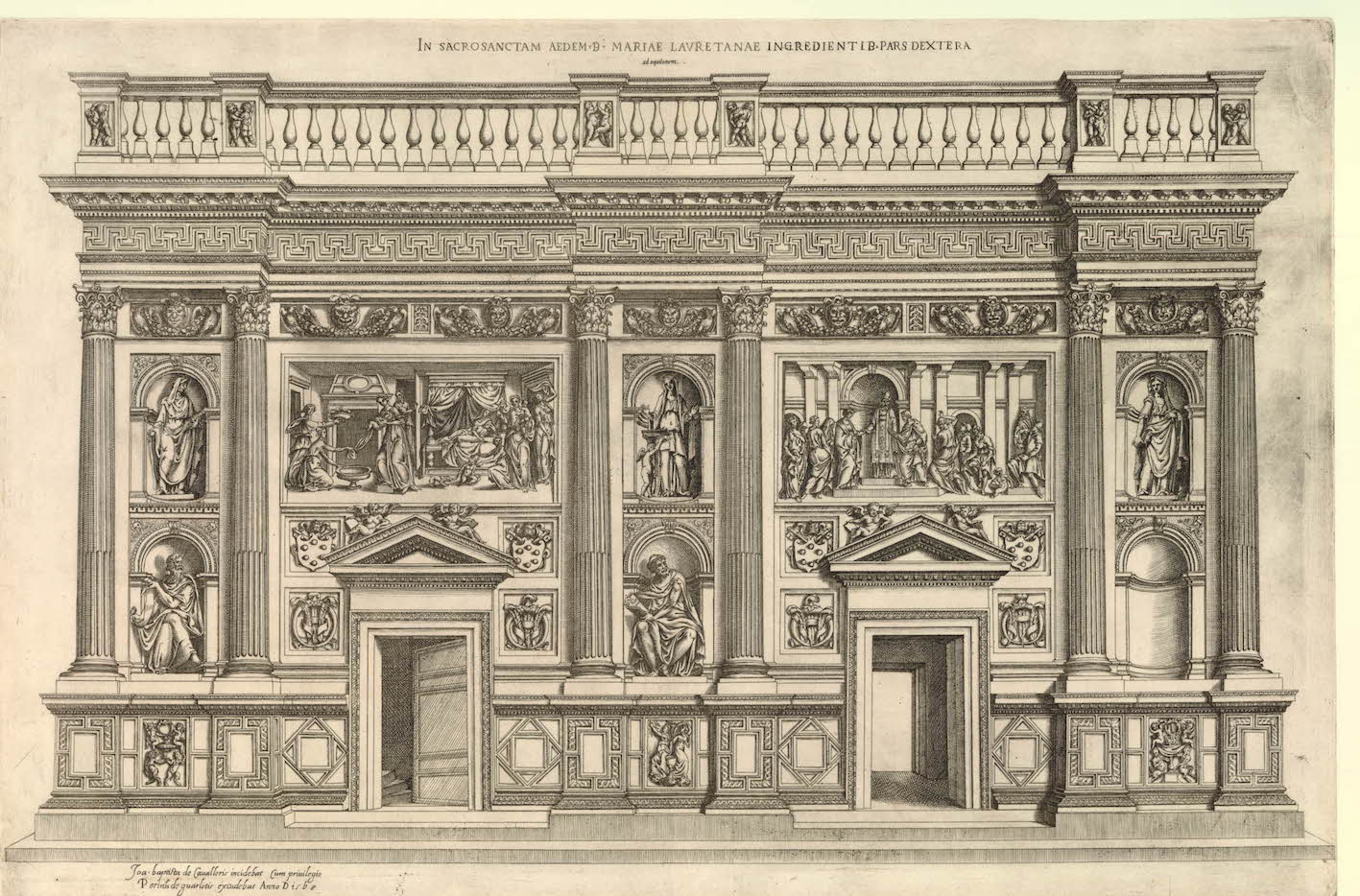

Adam Philippon’s 1649 Parisian publication Le veritable plan, et pourtrait de la Maison Miraculeuse de la S.te Vierge, ainsy qu’elle se voit á present á Lorette offers a detailed vision of a popular pilgrimage site on the Italian peninsula (Fig. 1). The text purports to record visually the divine structure, which is believed to have been the home of the Virgin and site of the Annunciation that relocated miraculously to Loreto, a town on the eastern coast of Italy in the late-thirteenth century. Dedicated to the Abbess of Notre Dame de Ligueux and printed with permission of Louis XIV, the book includes etchings of all four walls of the structure’s opulent exterior, which was appended to the cult site over the sixteenth century (Figs 2 & 3).

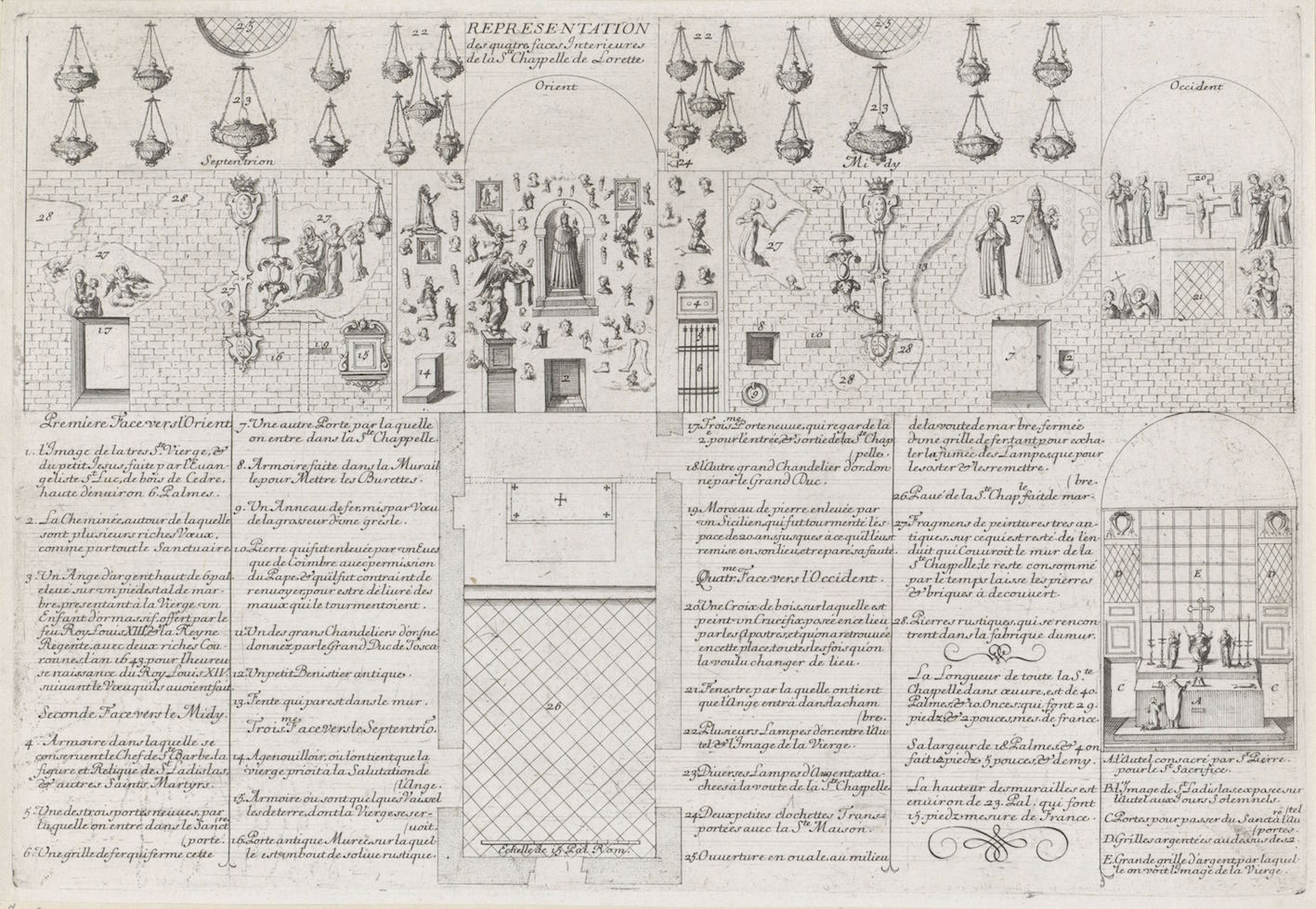

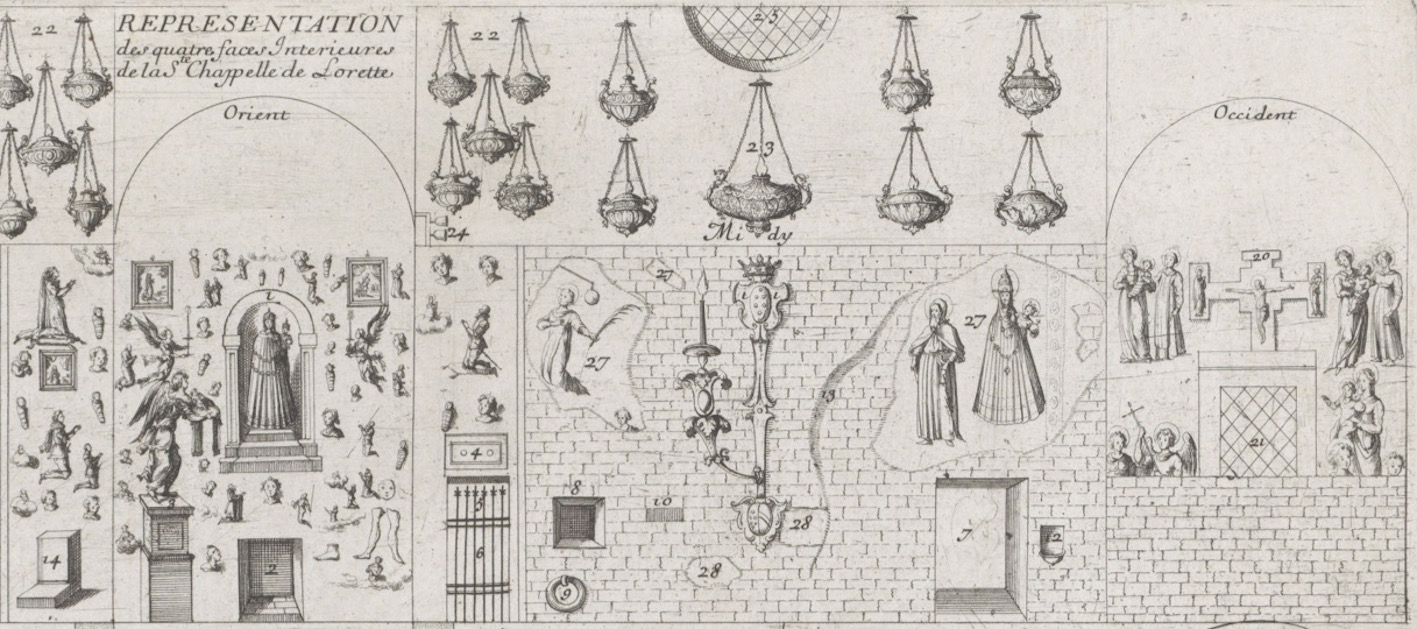

The publication culminates with a single print detailing the four internal walls, complete with crumbling frescoes that reputedly predate the building’s divine transport, and lend credence to claims of continuous adoration by the Christian community (Fig. 4). But the structural interior portrayed does not represent the Santa Casa at Loreto. Rather, Philippon’s print renders a replica of the architectural relic constructed on the Venetian island of San Clemente (Figs 5 & 6).

Across the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, many Catholic communities recreated the Santa Casa of Loreto for regional devotion. In my own explorations stemming from the ERC-funded research group SACRIMA at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich, I have already identified over 250 replicas across Europe, in Poland, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Hungary, Germany, Italy, Slovakia, Croatia, Austria, Switzerland, France, and Belgium (project ongoing).

But how does an architect or patron effectively recreate space in the early modern period? In the case of the Santa Casa, minutely detailed prints circulated the structure into a variety of locations and uses. Woodblock, engraved and etched prints emanated from the cult epicenter in Le Marche, but also from other communities invested in Loretan devotion, from which patrons commissioned two- and three-dimensional replicas. One such community was Venice.

A Venetian Origin

Venetians harbored a strong devotional connection to the Loretan Santa Casa. La Serenissima claimed deep associations with the Virgin Mary down to the city’s very foundations, which reportedly occurred on the day of the Annunciation, 25 March 421. The city was a popular point of departure for pilgrims travelling by boat to the Marchan region en route to the cult site at Loreto. Furthermore, the local government laid contested territorial claims on the eastern Adriatic coast where the Santa Casa had purportedly resided for a brief three years in Trsat (modern-day Rijeka) before relocating to Italy.

As such, Venetians placed great emphasis on the Annunciate roots of the structure, elevating the Virgin and her home on par with other protectors of the state, such as Saints Roche and Pantaleon. Commissioned by Monsignor Francesco Lazzaroni, vicar of the local church of Sant’Angelo, the construction supplanted the patron’s original promise to pilgrimage to Loreto in thanks for the Virgin’s intercession in the 1630 plague outbreak, which ravaged the Venetian community.

Philippon’s print offers rich visual cues to its Venetian model, including various changes made to the internal fresco program by its artists and patron, like the prominent portrayal of the Madonna of Loreto cult statue above the door of the southern wall, to the right of the high altar (Figs 7 & 8). The iconic, sculptural form of the Madonna of Loreto wearing her papal crown stands with an attendant saint, adorned in an enveloping white robe encircled with gem-encrusted golden chains. This representation prioritizes the local fanfare associated with the Marian cult statue over the original wall decoration at Loreto, which consists of an archaized decorative program of saints and donors before an enthroned Virgin and Child.

The sculpture was the devotional priority for Venetians, having venerated the image for years at the church of Santa Maria della Carità (sadly, the sculpture no longer survives). According to a Breve descrizione della chiesa, the sculpture processed to the Laguna shrine in 1646, accompanied by a vast retinue of gondole conveying local nobility, members of various religious orders, and the lay populous out to the island, many of whom bearing lit torches and playing musical instruments in jubilant celebration. Instead of the devout travelling to Loreto, the Santa Casa had effectively come to Venice.

Authorial Sources

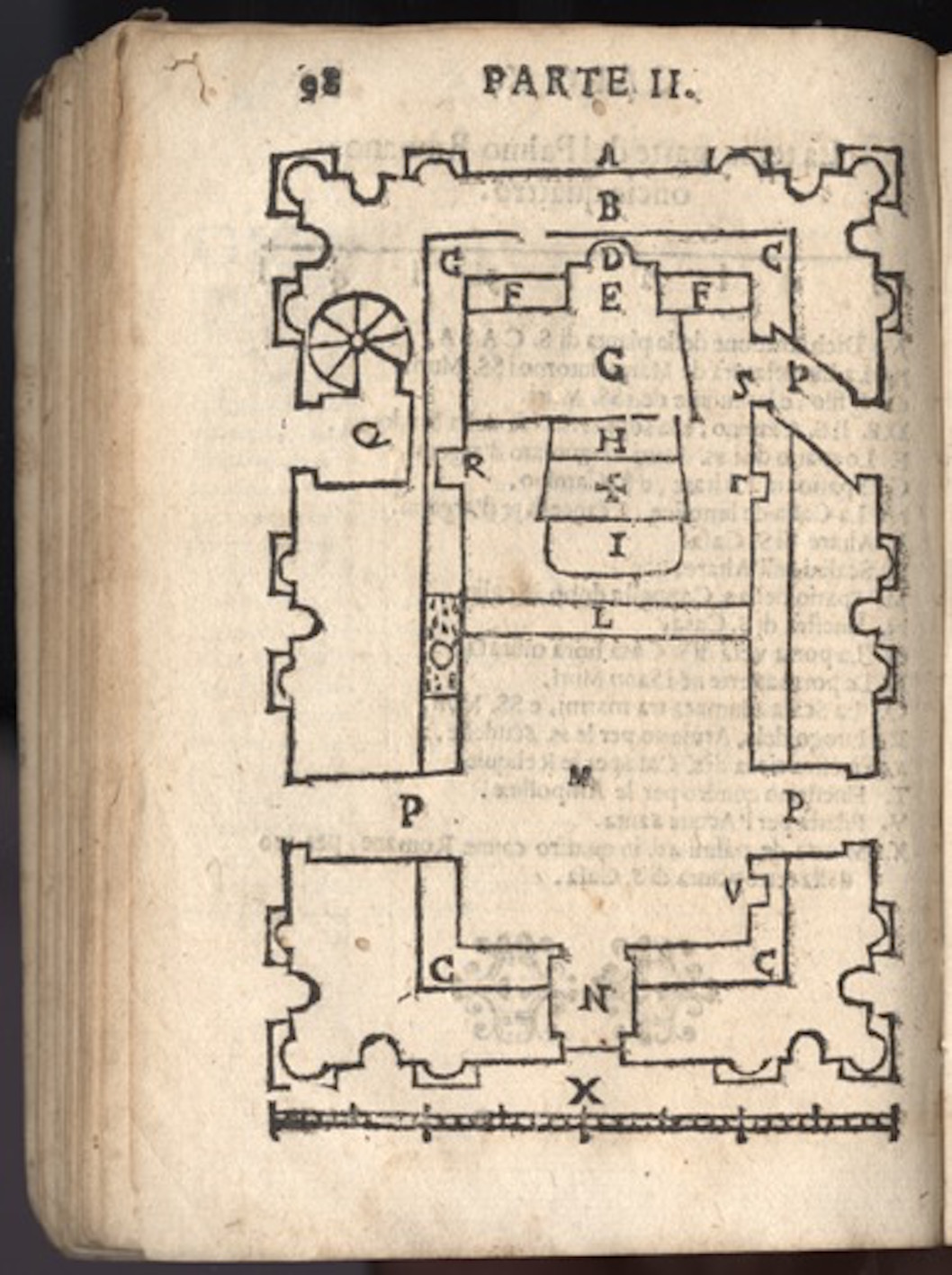

Though the etching alleges to reproduce the original structure in Le Marche, in reality the image is more of a composite, emerging from multiple sources simultaneously. The external views of the Santa Casa appear to be based on Giovanni Battista de’ Cavalieri’s engravings of the 1570s (Fig. 9), with added detail to flesh out those sculptural additions then incomplete during Cavalieri’s Loretan sojourn (note the empty niche in the bottom right corner of the northern façade). The floorplan may have emerged from any number of publications on the Holy House, like Silvio Serragli’s 1639 edition of the La Santa Casa Abbellita (Fig. 10).

While I do not think Philippon’s publication was intentionally misleading, his printed book calls into question the image represented. When we gaze upon this Santa Casa interior, are we transported inside the original at Loreto, or do we conceptually enter the Venetian iteration? Whose votive offerings do we see levitating around the Marian sculpture in the altar niche? Philippon’s publication layers multiple documentary dimensions into its construction, composed of textual accounts and preexisting schematic images - like the many editions of Serragli’s text - and “verified” through regional recreations like the Laguna shrine.

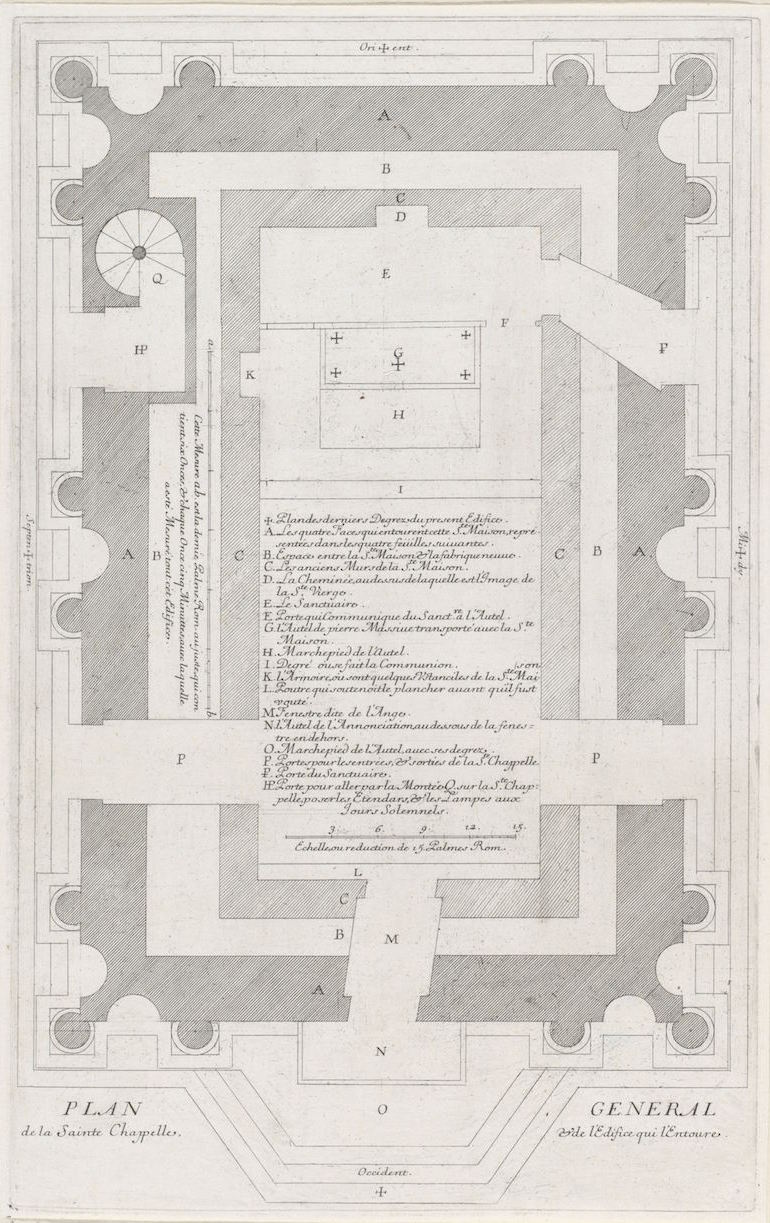

Though the compilation of information from various arenas is far from revolutionary, the layout of the single-print folio of the Santa Casa interior is remarkable. This folio differs from all of the other prints in Philippon’s publication. Prints of the structural exterior each offer a single wall of the Santa Casa’s sixteenth-century revetment program. Likewise, a separate floorplan visually describes the layered effect of—and relationship between—the external and internal walls, as well as the altar directly before the western façade (Fig. 11).

By contrast, the Santa Casa interior (Figure 4) is a cluttered compilation: all four walls appear at once on a notably smaller scale, crowded onto the page with a second floorplan, freestanding altar, and explanatory key. The exacting detail manifested on the individual pages of the Santa Casa exterior seems to have been outweighed by an innate urge to perceive the complete edifice at once. In essence, Philippon’s interior reproduces the whole relic body of the building before the viewer’s eyes. The textual key and narrative descriptions below further invites the viewer to peruse the miniature representation intimately, and in so doing contemplate on the whole Santa Casa.

In this crowded representation of the relic body, Philippon’s publication builds on yet another precedent. In the early seventeenth century, rulers and patrons of Catholic territories vied for increasingly accurate structural information: certain, unnamed German princes, according to Serragli, requested images “in Stampa” of the friars at Loreto circa 1625. The only surviving copperplate housed in the Loreto museum similarly represents the four walls and altar shrine, though the walls are stacked vertically rather than linked in a horizontal chain. Philippon’s representation therefore elaborates on a preexisting format, adapting a visual mode to package the entire Santa Casa on a single page.

Paper Models and Proliferation

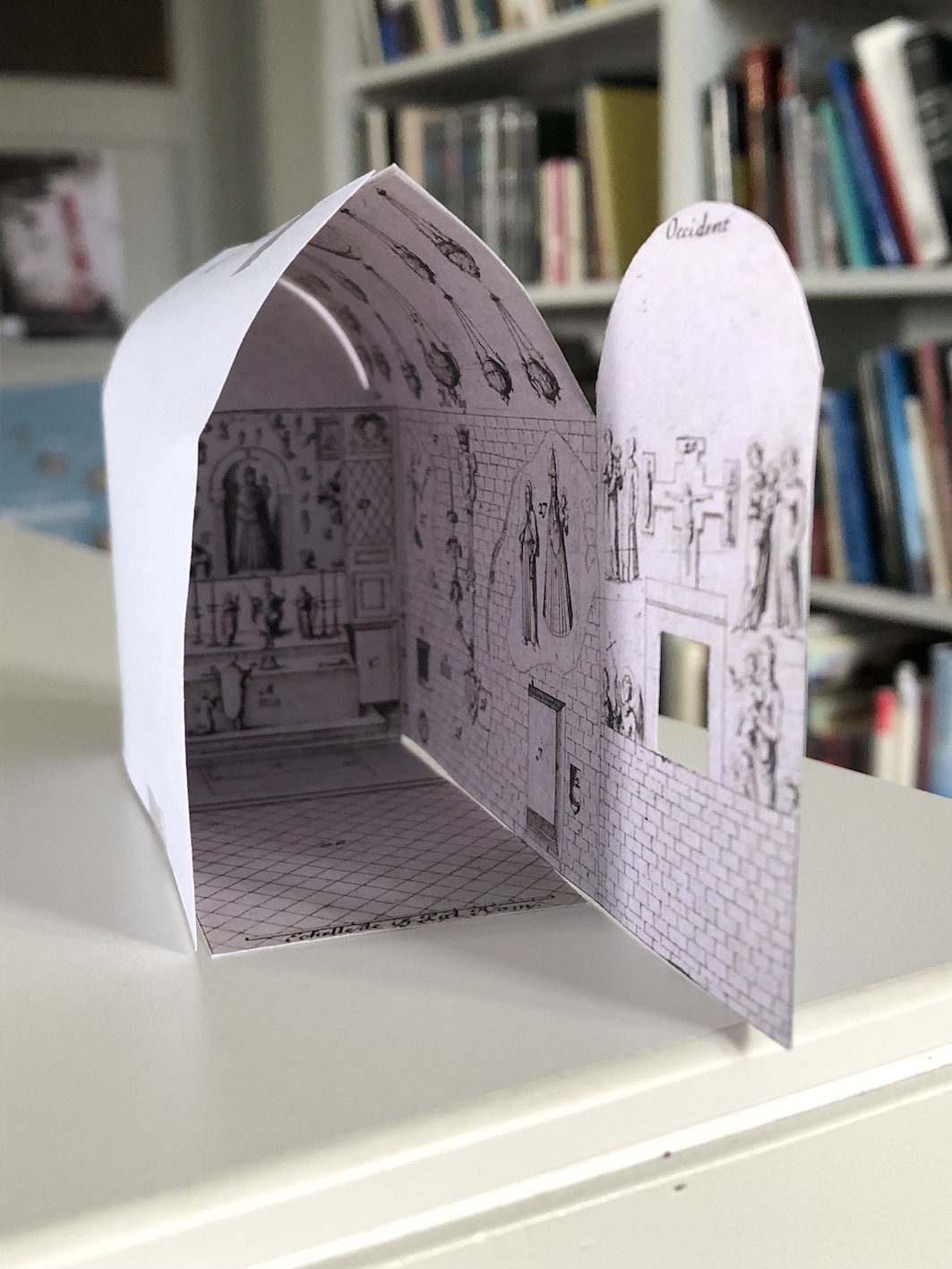

Philippon’s publication renders a normative vision of the Santa Casa based on myriad authoritative sources, albeit the result is not strictly speaking a product of Loreto. The format is also particular: why limit the structural information conveyed by linking the four walls horizontally across the page? This detail offers another clue to the print’s potential purpose. Should the owner cut apart the image, the walls fold together around the building’s floorplan, which emanates directly from the foundations of the niche wall.

The elongated lateral sides of the Holy House curve together at the top to form the barrel vault over the interior, from which richly ornate golden and silver lanterns hang to illuminate the miraculous space (Figs 12 & 13). What the viewer has lost in terms of detail from the diminutive scale of the encapsulated image, they gain from a highly interactive representation. Like the large-scale paper models investigated in the recent work of Giovanni Santucci, these Santa Casa prints recreate the sacred building by raising the walls around its devotional core, allowing the viewer to conceptually possess their own Holy House.

That Philippon’s publication emerges from Paris and not Venice indicates the wide influence of the Venetian replica on other early modern versions. Philippon’s engravers either copied Venetian prints of the regional Santa Casa, or worked directly from the Laguna shrine, likely presuming the seventeenth-century version to be a reliable source. Surviving Venetian-style Holy Houses appear throughout the Veneto and in nearby Slovenia, but also in communities as far away as Gołąb in eastern Poland (Figs 14 & 15).

Whether the print was used for conceptual or literal construction - in paper, or brick and mortar - Philippon’s image carried Venetian priorities of the sculptural cult object into France, where it conceivably impacted other Santa Casa replicas. Sadly, the mass destruction of religious sites during and after the French Revolution has obliterated almost all signs of local Loretan devotion. Hopefully as this research progresses, the length to which Philippon’s Representation influenced seventeenth-century devotion will come to light (Fig. 16).

Bibliography

Biblioteca Correr, Breve descrizione della Chiesa, che si trova nell’Isola di S. Clemente MSS, circa 1680.

Brown, Patricia Fortini. “The Self-Definition of the Venetian Republic,” in City States in Classical Antiquity and Medieval Italy, ed. by Anthony Molho, et al., p. 511-548. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1991.

Carraro, Martina, ed. L’Isola di San Clemente a Venezia. Storia, restauro e nuove funzioni. Venice: CARSA Edizioni spa, 2003.

Gaier, Martin. Facciate sacre a scopo profane. Venezia e la politica dei monumenti dal quattrocento al settecento. Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2002.

Giffin, Erin. “The Tradition of Change in Copies of the Santa Casa di Loreto: The Case of San Clemente in Venice,” Contested Forms: Sacred Images and Normativity in Early Modern Art. Turnhout: Brepols (forthcoming December 2019).

Philippon, Adam. Le veritable plan, et pourtrait, de la maison miraculeuse de la S.te Vierge, ansy quelle se voit a presente à Lorette; avec toutes ses particularez marques sur le plan par ordre alphabetique. Le tout dessine et mesure sur les lieux: Avec un petit abregé de tout ce qui s’est passé en ses divers trasports. Paris: Pierre Mariette, 1649.

Ranucci, Mara, Massimo Tenenti. Sei riproduzioni della Santa Casa di Loreto in Italia. Loreto: Congregazione Universale della Santa Casa, 2003.

Santucci, Giovanni. “Federico Brandani’s paper model for the chapel of the Dukes of Urbino at Loreto.” The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 116 (2014): p. 4-11.

Serragli, Silvio. La Santa Casa Abbellita, Loreto: Paolo e Giovanni Battista Serafini Fratelli, 1634 and 1639 editions.